Parthenon (Nashville)

The Parthenon | |

The Parthenon in Nashville's Centennial Park is a full-scale copy of the original Parthenon in Athens. | |

| Location | Nashville, Tennessee, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°8′59″N 86°48′48″W / 36.14972°N 86.81333°W |

| Built | 1897 (original structure) 1925–1931 (permanent version) |

| Architect | William Crawford Smith[2][3] |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001236[1] |

| Added to NRHP | February 23, 1972 |

The Parthenon in Centennial Park, Nashville, Tennessee, United States, is a full-scale replica of the original Parthenon in Athens, Greece. It was designed by architect William Crawford Smith[4][5] and built in 1897 as part of the Tennessee Centennial Exposition.

Today, the Parthenon, which functions as an art museum, stands as the centerpiece of Centennial Park, a large public park just west of downtown Nashville. Alan LeQuire's 1990 re-creation of the Athena Parthenos statue in the naos (the east room of the main hall) is the focus of the Parthenon just as it was in ancient Greece. Since the building is complete and its decorations were polychromed (painted in colors) as close to the presumed original as possible, this replica of the original Parthenon in Athens serves as a monument to what is considered the pinnacle of classical architecture. The plaster replicas of the Parthenon Marbles found in the Treasury Room (the west room of the main hall) are direct casts of the original sculptures which adorned the pediments of the Athenian Parthenon, dating to 438 BC. The surviving originals are housed in the British Museum in London and at the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

History

[edit]

Nashville's nickname, the "Athens of the South",[4] influenced the choice of the building as the centerpiece of the 1897 Centennial Exposition. A number of buildings at the exposition were based on ancient originals. However, the Parthenon was the only one that was an exact reproduction. It was also the only one that was preserved by the city, although the Knights of Pythias Pavilion building was purchased and moved to nearby Franklin, Tennessee.

Major Eugene Castner Lewis was the director of the Tennessee Centennial Exposition and it was at his suggestion that a reproduction of the Parthenon be built in Nashville to serve as the centerpiece of Tennessee's Centennial Celebration. Lewis also served as the chief civil engineer for the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railroad. Originally built of plaster, wood, and brick,[6] the Parthenon was not intended to be permanent, but the cost of demolishing the structure combined with its popularity with residents and visitors alike resulted in it being left standing after the Exposition.

In 1895, George Julian Zolnay was "employed to make models for the ornamentation" for the building.[5] Within the next 20 years, weather had caused deterioration of the landmark; it was then rebuilt on the same foundations, in concrete, in a project that started in 1920; the exterior was completed in 1925 and the interior in 1931.[7] Local architect Russell Hart was hired for the reconstruction.[7]

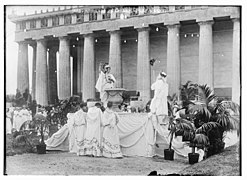

Some of the most elaborate events that occurred at the Parthenon were the Spring Pageants of 1913 and 1914. These extravaganzas were theatrical productions. With casts of up to 500, the pageants attracted audiences from surrounding states and rail prices were lowered to encourage attendance. The city of Nashville celebrated the "Athens of the South". The 1913 performance was entitled The Fire Regained, a play written by Sidney Mttron Hirsch, and featured a mythological story line enhanced by theatrical spectacle popular in that era.[8] The 1914 production, The Mystery at Thanatos, had a similarly mythological plot, but was shorter and better received. A copy of the script is on file at the Nashville Public Library. Both shows featured displays ranging from chariot races to large dance numbers to thousands of live birds to set pieces that shot flames, all set against the backdrop of the Nashville Parthenon.

Current use

[edit]As an art museum, the Parthenon's permanent collection on the lower level exhibits 63 paintings by 19th and 20th century American artists, donated by James M. Cowan in 1927–1929.[7] Additional gallery spaces provide a venue for temporary shows and exhibits. The main level contains a replica, completed in 1990,[7] of the Athena Parthenos statue that was in the original Parthenon in Athens.

In 1982, Alan LeQuire was commissioned to create the statue of Athena Parthenos[7] as a reconstruction, to scholarly standards, of the long-lost original: she is cuirassed and helmeted, carries a shield on her left arm, a 6-foot-high (1.8 m) statue of Nike (Victory) in her right palm, and stands 42 feet (13 m) high, gilt (as of 2002)[7] with more than 8 pounds (3.6 kg) of gold leaf; an equally colossal serpent rears its head between her and her shield. Some followers of Goddess Spirituality practices have left ritual offerings near the statue.[9]

In the summertime, local theater productions use the building as a backdrop for classic Greek plays such as Euripides' Medea and Sophocles' Antigone, performing (usually for free) on the steps of the Parthenon. Other performances, such as Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses, have been held inside, at the foot of Athena's statue.

In 2001, the Nashville Parthenon received much needed cleaning and restoration of the exterior.[7] The exterior lighting was upgraded to allow the columns of the building to be illuminated with different colors than the facade.

In popular culture

[edit]The Parthenon served as the location for the political rally in the climactic scene of Robert Altman's 1975 film Nashville.[10]

It was used as a backdrop for the battle against the Hydra in the 2010 film Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief.[11]

It features in the title and lyrics of the song "Nashville Parthenon" from the album Etiquette, by Casiotone for the Painfully Alone, as well as the song's 2011 sequel "Goodbye Parthenon".

It was used in the 2000 PBS series Greeks: Crucible of Civilization.

A poem titled "Ganymede" in Heather Ross Miller's Celestial Navigator: Writing Poems with Randall Jarrell features the Parthenon.

The structure figures in the climax of the Hector Lassiter novel Three Chords and The Truth, by Craig McDonald.

Gallery

[edit]

-

Statues

-

The center of the statues

-

A closer look at the Shield of Athena Parthenos

-

Greek play, circa 1913 or 1914

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register of Historical Places - Tennessee (TN), Davidson County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 3, 2007.

- ^ Coleman, Christopher K. (Fall 1990). "From Monument to Museum: The Role of the Parthenon in the Culture of the New South". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 49 (3): 140. JSTOR 42626877.

- ^ "Valor's Reward Paid His Memory. Tablet Unveiled to the Memory of Col. C. W. Smith. On Walls of the Parthenon. Rare Tribute Paid the Name of Soldier-Architect. Tully Brown and Lieut. Caruthers Deliver Addresses of Occasion Before Several Hundred People, Among Whom Were Comrades of Two Wars". The Nashville American. Nashville, Tennessee. July 6, 1903. pp. 5, 7. Retrieved November 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Creighton, Wilbur F., The Parthenon In Nashville: Athens of the South, From a personal viewpoint, JM Press, Brentwood, Tennessee, 1989, revised edition 1991

- ^ a b Creighton, Wilbur F., The Parthenon In Nashville: From a personal viewpoint, 1968, self published pp. 21–22

- ^ "Nashville.gov – Parks and Recreation, Parthenon – Parthenon Timeline". November 20, 2012. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Timeline at the Parthenon". Metro Parks and Recreation Department, Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Stewart, John Lincoln (1965). The Burden of Time: The Fugitives and Agrarians. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–34. ISBN 9781400876266. OCLC 859825119. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Ciaccia, Olivia (2022-04-06). "Seeking Sekhmet: The veneration of Sekhmet Statues in contemporary museums". Pomegranate. 23 (1–2). doi:10.1558/pome.18653. ISSN 1743-1735.

- ^ Stuart, Jan (2003). The Nashville Chronicles: The Making of Robert Altman's Masterpiece. New York, New York: Limelight. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-879-10981-3.

- ^ "City Hopes To Build Madison Nature Center – Community News Story – WSMV Nashville". July 3, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1925 establishments in Tennessee

- Museums in Nashville, Tennessee

- Art museums and galleries in Tennessee

- Buildings and structures in Nashville, Tennessee

- Buildings and structures completed in 1925

- Greek Revival architecture in Tennessee

- Replica buildings

- World's fair architecture in Tennessee

- Museums of ancient Greece in the United States

- Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition

- Temples of Athena

- National Register of Historic Places in Nashville, Tennessee